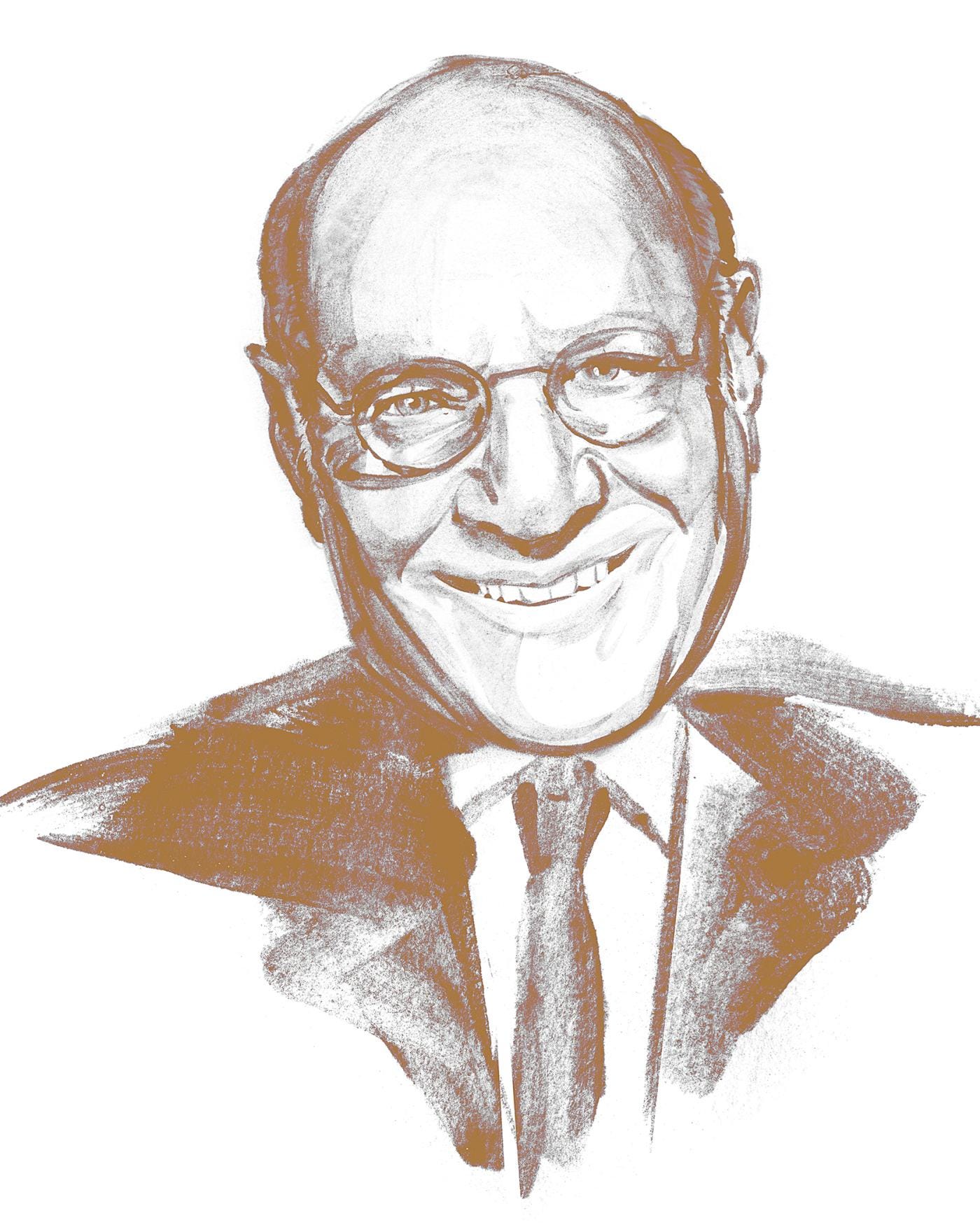

Earn Your Luck: Barry Diller on Serendipity, Sexuality and Success

In a new memoir, ‘Who Knew,’ Diller credits luck over talent in helming multiple Hollywood studios and television networks: ‘It’s the timing, stupid.’

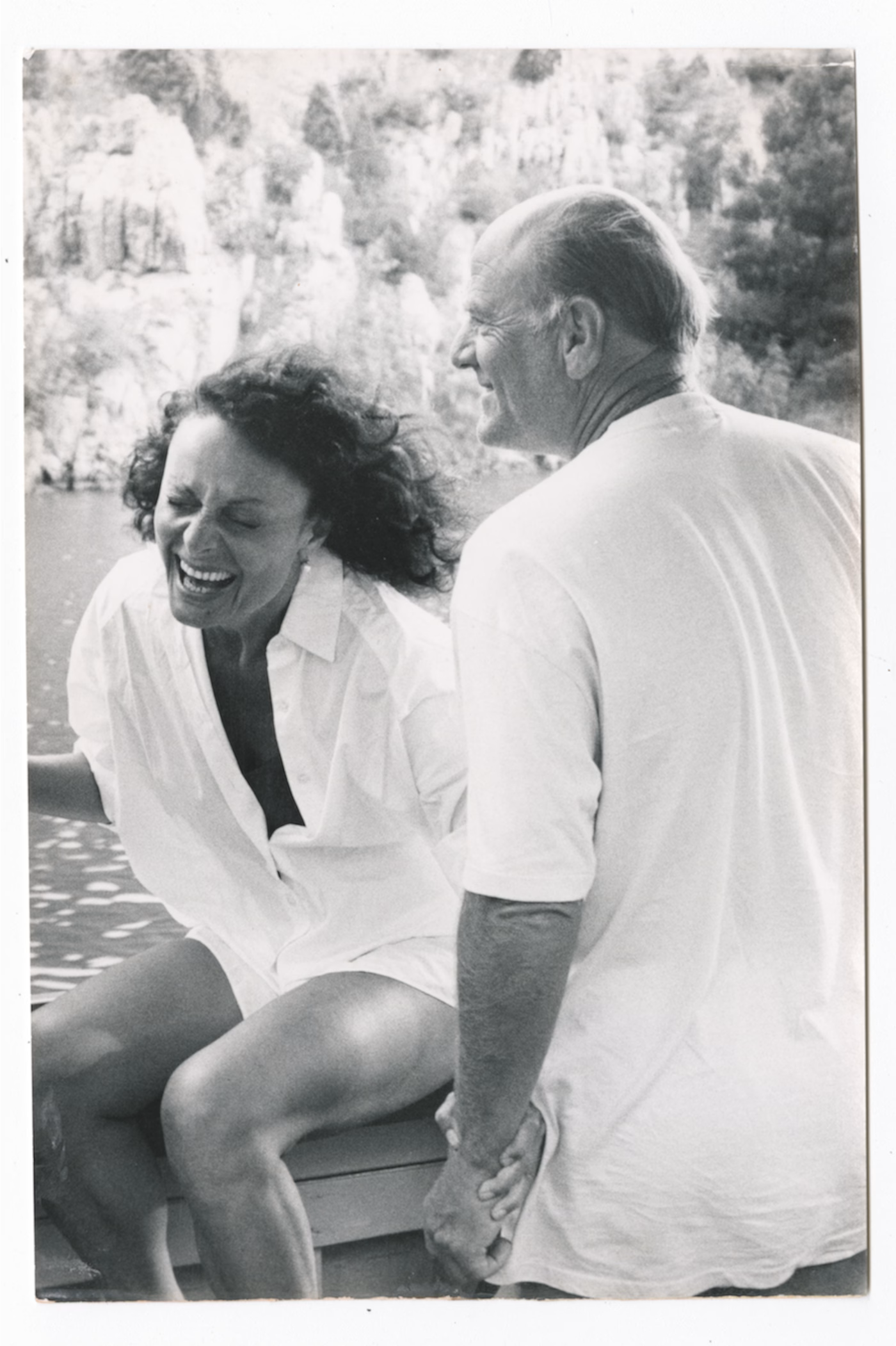

ICONOCLASTS DON’T waste their time or ours. We know entertainment mogul Barry Diller bested most of his rivals, although a few—notably Sumner Redstone—outmaneuvered him. So when Diller takes his gloves off in his new memoir, he confronts what we couldn’t see. His backstage positioning to chomp entire companies whole; the contrast between working for someone else versus for himself; and, on a personal level, his demons. Case in point, Diller on his attraction to men: “I had wanted so desperately to alter my sexuality as a child and teenager and I had tried so hard and failed. I was left with an unquenchable need to be vigilant about every other aspect of my life.” On his much gossiped-about relationship with his now-wife, Diane von Furstenberg: “We aren’t just friends. Plain and simple, it was an explosion of passion that kept up for years.”

Diller broke out of the William Morris mailroom at age 24 and turned the Movie of the Week at ABC into must-see TV, producing hits including Go Ask Alice and Brian’s Song. Ever heard of Saturday Night Fever or Raiders of the Lost Ark? Both came out during his decadelong stewardship of Paramount from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s. After more than seven years running a second major studio, Twentieth Century Fox, and releasing blockbusters such as Home Alone, he left Hollywood and went on to acquire the Home Shopping Network (HSN). Before most of his peers understood the term interactivity, Diller had seized on the commercial potential of merging telephones and televisions. He also made a series of strategic acquisitions that transformed his media holdings into a diversified digital empire under IAC (formerly InterActiveCorp).

Unlike many entertainment or business icons who write memoirs to bolster legacies and egos, Diller faces facts: No one can run or reposition several studios and networks without a few spectacular swan dives. He remembers a time in the mid-1990s when he was “a mogul manqué,” “nationally known damaged goods,” after losing his bid to buy Paramount. He recounts “glorious dead ends” and how Google “manhandled” him out of opportunities. But he never let these setbacks hamper his momentum. Instead, he owned the simple truth: They won. We lost. Next.